The best fiction of 2024 | Best books of 2024

iyear of surprises – a posthumous fable by Gabriel García Márquez, a superhero collaboration between China Miéville and Keanu Reeves – the biggest news, as always, was a new novel by Sally Rooney. Intermezzo (Faber) landed in September: the story of two brothers mourning their father and coming to terms with each other and the women in their lives, it’s a heartfelt exploration of love, sex and grief. With one direction exploring the perspective of the neurodiverse younger brother and conflicting stream of consciousness for the older one, it opens up a more fruitful direction after 2021’s Beautiful World, Where Are You?

A new novel by Alan Hollinghurst is always an event and in the Our dinners (Picador) he is at the top of his game, charting Britain’s changing mores through the prisms of class, race, politics and gender in the memoir of a half-Burmese actor whose state school scholarship catapults him into the world of privilege. Tender, elegiac and exquisitely detailed, it’s a masterful recreation of the gay experience over the past half century.

There was a different approach to the great social novel than Andrew O’Hagan, whose Caledonian Road (Faber) is a riotous state-of-the-nation burlesque: centered on the downfall of a celebrity art historian, it digs energetically through the layers of London, from the aristocracy and cultural elite to Russian drug lords to disenfranchised youth. Meanwhile, the provocative Choice by Neel Mukherjee (Atlantic) juxtaposes three distinct narratives, ranging from climate anxiety among the metropolitan elite to poverty in rural India, to pose difficult questions about globalization and morality.

Other notable returns include Sarah Perry, who in Enlightenment (Jonathan Cape) traces patterns of unrequited love and cosmic wonder against the path of Comet Hale-Bopp, all done with her usual grace and punch of atmosphere. Evie Wilde’s poignant, unconventional ghost story, channeling family trauma and conflicted love, The echo (Nose), establishes her as a great talent; as well as Charlotte Wood’s diary of a woman who retires to a convent, Stone Yard Devotional (Scepter), which subtly explores forgiveness, responsibility and despair in the face of the world’s horrors.

Ingrid Persaud’s ensemble for a real-life Trinidadian gangster, Boysi Singh’s Lost Love Songs (Faber), is a triumph of voice, while that of Anita Desai Rosarita (Picador), her first novel in a decade, is a rewarding mystery about family heritage and historical trauma. Fugitive Pieces author Ann Michaels doesn’t post often either; Detained (Bloomsbury), an elliptical meditation on war and love, illuminates moments of human connection and transports the reader. Crooked seeds by Karen Jennings (Holland House) stands out for its uncompromising vision: focusing on a bitter, broken white woman in post-apartheid South Africa, he fearlessly works through difficult seams of rights and collective guilt.

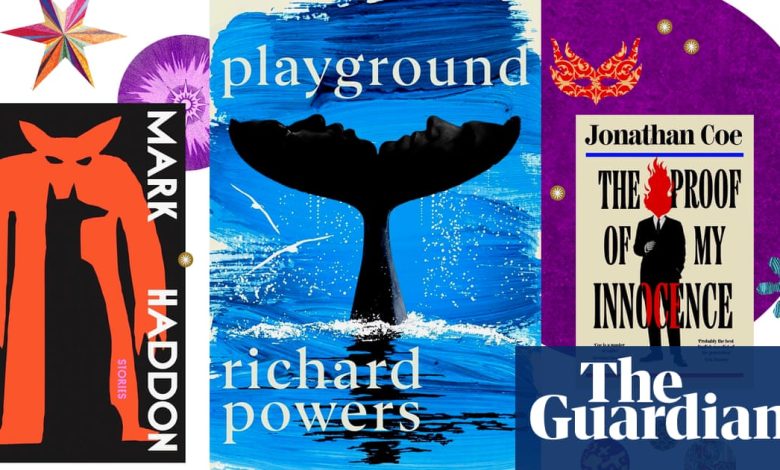

Two comics masters have published new novels: You are here by David Nicholls (Scepter) follows the improbable romance of an odd middle-aged couple as they walk around the Lake District, struggling with emotional baggage as well as their rain-soaked rucksacks: it balances the absurd and the sad with an apparently casual ease. c The proof of my innocence (Viking), Jonathan Coe spins a cozy crime parody around the rise and rapid fall of Liz Truss; this playful, metafictional madness is hugely entertaining.

Over the summer, Taffy Brodesser-Ackner followed up her landmark debut Fleishman Is in Trouble with a chronicle of American wealth and intergenerational trauma, Long Island Compromise (Forest fire); while for engrossing beach reads, Marina Kemp’s elegantly written saga of a family held captive by a novelist patriarch at the helm, The Unwild (4th Estate), was hard to beat.

Miranda Juli brought comic verve to her auto-fictional account of midlife doubts and desires, Fours (Canongate), in which an artist takes a strange journey to the heart of his own changing identity. This witty, honest, no-holds-barred and decidedly unconventional novel explores women’s impulses toward creativity and self-expression.

It’s been a strong year for American fiction everywhere, from the widescreen realism of Richard Powers Children’s playground (Hutchinson Heinemann), an epic celebration of marine life and a meditation on progress and artificial intelligence, to Percival Everett’s magisterial satire James (Mantle), a major reworking of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, and Rachel Kushner’s breathtaking espionage romp The lake of creation (Cape), which reveals how we construct politics, history and ourselves. I was on this year’s Booker Prize jury, which shortlisted all three, but in the end we gave the prize to a novel published last winter: Samantha Harvey’s superbly crafted novel Orbital (The Harvest), a new and profound perspective on the Earth in all its beauty and fragility, and vital reading in an age of environmental degradation and territorial violence.

Irish novels dominate in 2023; this year the shelves were full of Irish sequels, with satisfying follow-ups from Colm Tóibín in Long Island (Picador), Roddy Doyle c The women behind the door (Cape) and Donal Ryan c Heart, Buddy in peace (Double day). Elsewhere, Tommy Orange returned to the characters from his debut in Wandering stars (Harville Secker), bringing both impressive historical scope and poignant domestic intimacy to the story of a Native American family spanning two centuries. Pat Barker completed his Women of Troy trilogy with The journey home (Hamish Hamilton), another sparkling down-to-earth look at Greek myth that dramatizes the bloody showdown between Agamemnon and Clytemnestra. And Ali Smith started a new project: Glyph (Hamish Hamilton), the first in the duology, playfully charts the resistance of two children against a government dystopia of surveillance and control.

It was an excellent year for debut novels, many of them seething with energy and formal innovation. The lodgers (Granta) is poet Holly Pester’s sideways look at housing insecurity, exploring emotional rootlessness through one woman’s sublet while in The night alphabet (Riverrun) another poet, Joel Taylor, brings extraordinary linguistic ingenuity to a narrative about tattoo artists and violence against women. The uncategorizable Spent light by Lara Pawson (CB Editions), a hybrid of fiction and life writing, thrillingly traces the webs of connection that resonate outward from household objects and everyday life to reveal the dark underbelly of our globalized world. Rita Bullwinkel’s quirky portrait of teenage female boxers, Shot in the head (Daunt), is organized as a tournament in itself, while Anna Fitzgerald’s A girl in the making (Sandycove) is told through the eyes of a young girl who grows older with each chapter. The irresistible narrator of Only here, only now by Tom Newlands (Orion), a Scottish teenager in a 1990s poor manor, expresses his ADHD through a magnificent riot of prose. And in Ann Hawke’s The pages of the sea (Weatherglass), a girl is left with relatives on a Caribbean island when her mother sails to England to find work: this fresh look at the Windrush generation uses dialect to convey the young child’s thoughts with vivid immediacy. Portraits in the Palace of Creation and Destruction by Han Smith (JM Originals), a dystopian coming-of-age fable, uses confusion and ambiguity to explore propaganda and dissent.

i found The Borrowed Hills by Scott Preston (John Murray), a pitch-black Western set among the sheep farms of Cumbria, striking and powerful, while Colin Barrett’s Wild houses (Cape), a darkly comic tale of claustrophobia and violence in a small Irish town, is every bit as stellar as his celebrated short stories. Yael Van Der Wouden’s The Safekeep (Viking), which exposes the repression and strange desires of the post-Nazi era in the Netherlands, makes a dazzling hairpin turn two-thirds of the way through. Going home by Tom Lamont (Sceptre) is the gently comic, bittersweet story of a London man who finds himself responsible for a two-year-old boy, in all his delightful, demanding, exhausting energy. Meanwhile Ferdia Lennon’s invention and confidence Glorious feats (Fig Tree), which brings modern Irish to Ancient Sicily, makes him a writer to watch.

Other historical highlights include Kevin Barry The heart in winter (Canongate), a Tarantino-style doomed romance set in an 1890s American mining town. and Karis Davis clear (Granta), a short and surprising novel about mountains, loneliness and the loss of language that displays her trademark intimacy and expansiveness. In short stories, by Mark Haddon Dogs and monsters (Chatto & Windus) shapes myths and fables into vivid new forms, while the hilariously dark Eliza Clarke She is always hungry (Faber) mixes genres and breaks taboos.

Finally, a recent publication that deserves the widest attention. Andrew Miller is known for sharp and unnerving historical novels like Pure and Genius Pain, but in Earth in winter (Scepter), a study of two young marriages during England’s Great Freeze of 1962-3, he may have written his best book to date. The shadows of madness and World War II loom over a world on the brink of massive social change. Miller imbues his characters and their times with a subtle sheen that is not to be missed.