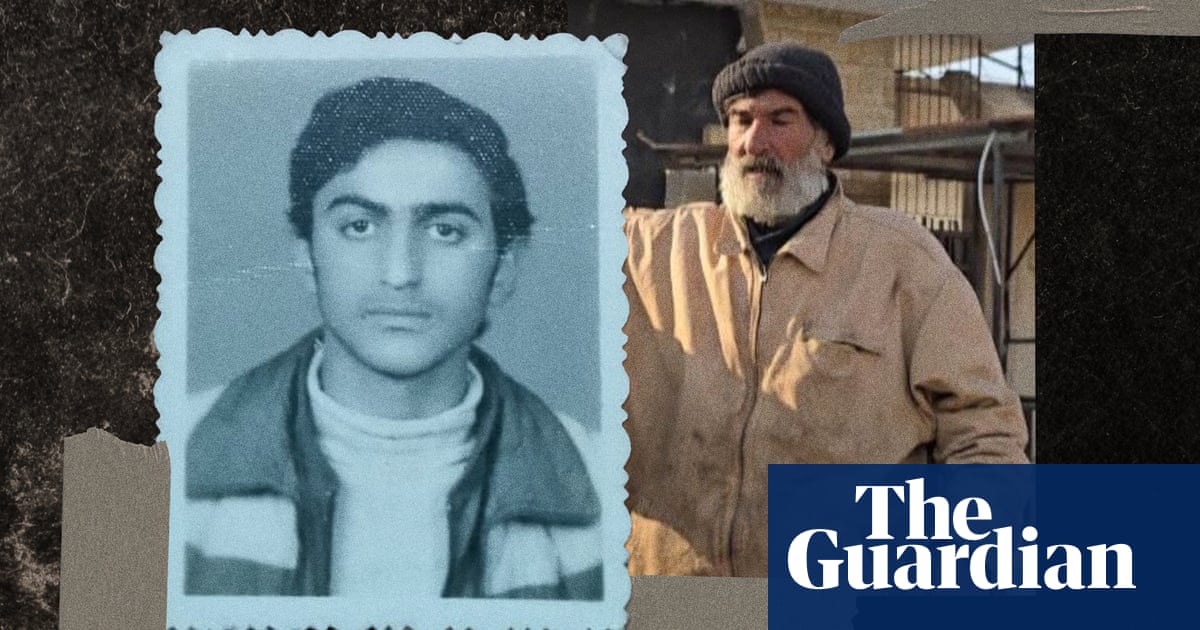

Moammar Ali has been searching for his older brother for 39 years.

In 1986 Syrian soldiers arrested student Ali Hassan al-Ali, then 18, at a checkpoint in northern Lebanon. Moamar has not heard from him since.

He spent the next three decades visiting various security services in Syria, where he received conflicting information about his brother’s whereabouts.

“There was no place in Syria that we did not visit. We went all over the country asking what happened to him. One day they would admit they had him in prison, the next day they would deny it,” said Ali, a resident of Akar, northern Lebanon.

The last information Ali received about his brother was that he was being held in a military security unit in Damascus on charges of political agitation. Then the Syrian revolution and subsequent civil war began, and Ali no longer received any updates on his brother’s condition.

Until Thursday night when Ali’s phone started buzzing. Friends, relatives and family members began sending him the same photo: a ragged man in his late 50s standing dazed outside Hama Central Prison in northern Syria.

“They said he looked like me. I told them, “that’s my brother!” The feeling is… indescribable. Imagine I haven’t seen him for 39 years and suddenly his picture is sent to you, how would you feel? Ali said.

His brother, who went to prison as an 18-year-old, was now 57. “He came out of prison an old man.”

Ali’s brother was one of thousands of prisoners released from Syrian government prisons in Aleppo and Hama after Islamist rebels led by Hayat al-Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) seized the city. In the past week, HTS-led forces have routed those of the Syrian army in northern Syria in a stunning offensive – the most serious challenge to Bashar al-Assad’s control of Syria since the 2011 revolution.

One of the first actions taken by the rebels in the newly captured cities was to release detainees from government detention centers. Video footage showed stunned people emerging from prisons, where jubilant crowds awaited them.

Syria’s prisons, where some 136,000 people were held until this week, are about a lot emblematic of government repression which earned Syria the title of “Kingdom of Silence”. Thousands of protesters were arrested during the revolution for speaking out against the government.

The leaked documents showed that the Syrian security apparatus viewed prisons as a key way to crush dissent and halt the momentum of peaceful protests. The vast network of security branches, detention centers and prisons has become proverbial for its brutal torture methods, which human rights groups have said are applied on an industrial scale.

“Many of those who had been forcibly disappeared before, we found that they had been killed. A significant number of them were killed under torture,” said Fadel Abdulghani, founder of the Syrian Network for Human Rights, who is originally from Hama.

Abdulghani said that while the release of political prisoners should be celebrated and encouraged, the indiscriminate, mass release of prisoners could carry significant risk – especially if perpetrators of violence were also released.

The sudden release of thousands of prisoners gave new hope to families who had not heard anything about the fate of their loved ones for years. Grainy screenshots of released detainees have been circulating on WhatsApp groups in Syria and neighboring countries as family members try to see if their relatives are among those released.

“You can’t imagine what it was like yesterday; many friends contacted me to ask about my father,” said Jinan, a resident of a border village in southern Lebanon who spoke under a pseudonym for fear of repercussions for her family’s security.

Jinan’s father was arrested in 2006 after crossing into Syria during the Hezbollah-Israeli war to find refuge for his family. “As soon as he arrived at our relatives’ house, there was a knock on the door and he was arrested,” Jinan said. She hadn’t heard from her father since.

Jinan and her family made several visits to Syria to inquire about her father’s release. After paying around $5,500 (£4,300) to various intermediaries, she was told that her father was being held at either Branch 235 or Sednaya prison, two detention centers in Damascus known for torture.

“We still have hope, I feel he is still alive and I think he will come back and live with us. I don’t support any armed groups that kill people, but if my father comes back… We need him,” Jinan said.

Confusion reigns as rapidly changing political dynamics in northern Syria make it difficult for authorities to identify who has been freed – and return them to their families.

Ali has still not been able to contact his brother directly and has spent the last 24 hours trying to track down who took the picture of him after his release from prison.

“When he comes home, we’ll have a big celebration. But until I smell it, until I can say, ‘There it is, my brother,’ nothing counts,” Ali said.